International Rivers

🔴 Communities are enduring unusual flooding & droughts from upstream #dams on the #Mekong. Concerns are being sidelined.

Countries «need to advocate for changes in the way dams are operated to reduce impacts on the river & communities downstream»@paideetes

Asia

How Mekong River is turning into a new flashpoint in Indo-Pacific

Date 12.08.2021

Author David Hutt

Experts view the South China Sea as the most probable area of conflict in Asia. Their attention now has also turned to the Mekong River, where the economic and environmental stakes are arguably much higher.

For several years, US politicians have adopted the Japanese slogan of a «free and open Indo-Pacific,» calling for international law to apply over disputes in the South China Sea, where China is accused of acting aggressively.

Earlier this month, during the East Asia Summit foreign ministers’ meeting, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called for «a free and open Mekong.»

The latest slogan points to the Mekong River’s importance to peace and stability in mainland Southeast Asia, as well as China’s alleged ambition to gain geopolitical advantage from riparian disputes.

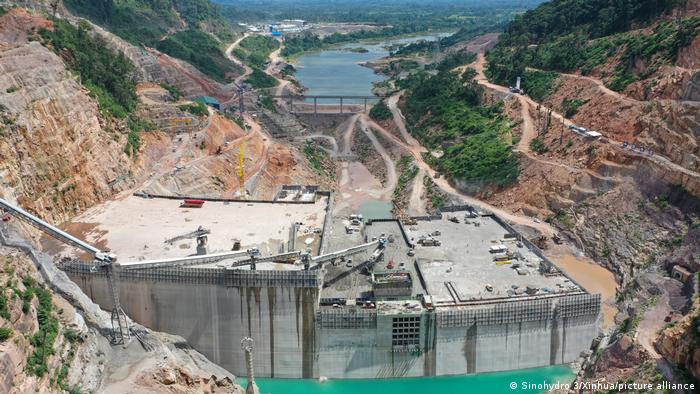

The Mekong River begins in China’s Tibetan Plateau and runs through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia before exiting in Vietnam’s delta region. Hundreds of hydropower dams have been built up and down the river since 2010, and most of them are in China and Laos.

Laos, the poorest member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc and a landlocked state without much of a manufacturing sector, has recorded a 7% GDP growth on average for much of the past decade, thanks in large part to exporting hydropower-generated electricity.

Environmental catastrophe overshadowed by political agenda

However, dam-building has resulted in environmental destruction and accusations of forced evictions and land-clearing across the region.

When part of a dam collapsed in southern Laos in 2018, at least 40 people were killed and hundreds of households in the region were affected by flooding.

The Mekong River begins in China’s Tibetan Plateau and runs through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia before exiting in Vietnam’s delta region

Thailand and Vietnam now also say they are experiencing unusual flooding and droughts because of damming on upstream parts of the Mekong.

Pianporn Deetes, the Thailand and Myanmar campaigns director for International Rivers, a global NGO, argues that an increased American and Chinese interest in Mekong has made the debate «more politicized and polarized.»

The concerns of riparian communities, she adds, are «being overshadowed or sidelined by political agenda.»

Critics say that China could threaten to intentionally hold back much of the river’s water upstream, producing extreme droughts in Thailand and Vietnam, as a way of pressuring Bangkok and Hanoi to accept Beijing’s geopolitical aims. In late July, Chinese hackers allegedly stole data on the Mekong River from Cambodia’s Foreign Ministry servers.

On the other hand, increased funding from US and China-led initiatives to governments and institutions in the region has «contributed to greater public attention and debate on issues critical to the future of the Mekong River and its people,» Deetes told DW.

Can the US and China cooperate?

On August 2, US Secretary of State Blinken co-hosted the second ministerial meeting of the Mekong-US Partnership, created in 2020 to expand the work of a previous forum, the Lower Mekong Initiative. The Beijing-led Lancang-Mekong Cooperation forum was formed in 2016.

«The US emphasis on transparency and inclusivity as part of its Mekong-US Partnership is enabling productive outcomes in the Mekong region and decreasing China’s accountability gap in its own backyard,» said Brian Eyler, director of the Stimson Center’s Southeast Asia program.

There are even claims that despite the conflict, the Mekong River could be one issue on which Beijing and Washington see eye-to-eye. «Environmental conservation of the Mekong is actually a major area of alignment for both the US and China,» Cecilia Han Springer, a senior researcher with the Global China Initiative at the Global Development Policy Center, told DW.

Tensions within Southeast Asia

Susanne Schmeier, an associate professor in Water Law and Diplomacy at IHE Delft, identifies two main tensions between China and the Southeast Asian states, and among the Southeast Asian states themselves.

«The data shows that Thailand is the biggest investor in hydropower dams in Laos, building four times as many dams as China,» said Eyler. Watch video 03:18

Mekong River threatened by dams and climate change

Thailand is also the biggest importer of electricity generated by Laos’ hydropower dams. But there is already an excess of power generated by the dams in Laos, so Vientiane has «a tall order ahead» to find markets for that power, Eyler added. «It would be wise to pause future dam building until this supply-demand problem is worked out.»

Deetes said, «As a key financier and buyer of electricity from Mekong mainstream and tributary dams in Laos, Thailand has a key role to play to reduce impacts on the Mekong and its people.»

In February 2020, the Thai government ended the China-led Lancang-Mekong Navigation Channel Improvement Project over its possible social and environmental impacts.

In January this year, Thai authorities rejected the new technical report issued by the Chinese developers of the $2 billion (€1.7 billion) Sanakham dam project in Laos, arguing it didn’t assess the environmental impact of downstream communities, mostly those in Thailand itself.

«Thailand should be more proactive in addressing the impacts of the Lancang cascade, including working with other Mekong countries, to advocate for the changes in the ways the dams are operated to reduce impacts on the river and communities downstream,» said Deetes.

Economic dependence on China

But how much influence other Southeast Asian states have over Laos remains in doubt. The bigger problem is whether Laos, as the so-called battery of Asia, could wean its economy off reliance on hydropower investments and exports.

Unlike its neighbors, Laos doesn’t have a large low-cost manufacturing sector. Its exports to the US and the European Union are negligible. The EU imported just €300 million worth of goods from Laos last year, according to European Commission data. Instead, the Lao economy remains heavily dependent on hydropower exports, mining and farming.

Watch video 07:27

Cambodia: Dam threatens Mekong’s dolphins

«I do not think Laos is likely to divert from its current strategy as the export of hydropower to neighboring countries provides a reliable and promising source of income,» said Schmeier.

Neither, Schmeier adds, does Laos’ government have many incentives to diversify its economy. The development of dams provides various opportunities for «additional personal income» for government officials and other actors, she noted.

And China, one of Laos’ closest political allies and trade partners, is a key investor in these projects.

Concerns have been expressed that Laos’ considerable debt to China puts it at risk of Beijing’s alleged «debt-trap diplomacy,» which could force it to sell important state assets away to China in lieu of repayments.

In 2020, a Chinese firm effectively took control of Laos’ domestic electricity grid.

After cataloguing the 100 largest hydropower projects in the Mekong region, Springer found that most of the hydropower projects in Laos plan to export up to 90% of electricity generated abroad. However, she adds, other renewable sources of energy, such as wind and solar, «can meet much of Laos’ electricity demand with similar revenue streams and less capital investment than if the current hydropower pipeline was built.»

https://www.dw.com/en/how-mekong-river-is-turning-into-a-new-flashpoint-in-indo-pacific/a-58842727